Hunter S. Thompson—best known as the pioneer of Gonzo journalism—was a writer whose influence stretched far beyond the realm of literature. Though not a photographer himself, Thompson had a profound and complex relationship with visual culture, particularly American photography. His perspective on photography offers a critical lens through which to examine shifting American values, journalistic integrity, and the cultural production of truth.

TLDR:

Hunter S. Thompson viewed American photography not just as an art form, but as a powerful tool for social commentary, aligned closely with his own journalistic ethos. He considered images a form of violent truth-telling that, like his writing, could expose the rot beneath the surface of American life. Though Thompson distrusted many institutional media outlets, he deeply respected photographers who captured raw, unfiltered realities. In this way, photography played a complementary role in shaping his critique of American culture.

The Convergence of Gonzo Journalism and Visual Truth

At the heart of Thompson’s Gonzo journalism was a deep distrust of sanitized media narratives and a commitment to subjective truth. This ethos naturally extended toward photography—an art form that, when practiced with integrity, delivered something that Thompson considered rare in journalism: unfiltered reality.

To Thompson, a powerful photograph was not just a captured moment—it was a loaded weapon of narrative, capable of challenging dominant ideologies and disrupting consumer complacency. He often worked closely with photographers, understanding their work to be an extension of his own mission: to illuminate the grotesque and the absurd with brutal clarity.

One of the most influential photographers in Thompson’s circle was Ralph Steadman, whose chaotic illustrations visually defined the Gonzo aesthetic. While not a traditional photographer, Steadman’s art served a similar purpose—it acted as an unsanitized visual truth in tandem with Thompson’s scathing prose.

Photography as a Political Weapon

In the tumultuous atmosphere of the 1960s and 1970s, the camera became a tool of rebellion. Photographers like Danny Lyon and Diane Arbus presented real, uncomfortable American narratives. Thompson admired this chaotic honesty and saw photography as a political act—just like his writing. In the Vietnam War era, this was crucial.

Key points of Thompson’s view on photography as a political tool:

- Authenticity over aesthetics: Thompson valued photos that were raw and real, not staged or polished.

- Subversion of official narratives: Photos that challenged governmental or media-sanctioned versions of events earned his admiration.

- Personal perspective: Like Gonzo journalism, photography needed a voice—something personal, embedded in the frame.

His appreciation for this visual insurgency was evident in his coverage of events like the 1972 presidential campaign, where the use of candid shots mirrored his approach to narrative journalism. To Thompson, framing a photo was as much about political choice as it was about composition. It was where the lens was pointed—and what was intentionally left out—that made the difference.

Cultural Impact: Documenting America’s Decline

If the American Dream was a lie, Hunter S. Thompson believed photography could help expose it. He saw photojournalism as a historical archive of betrayal, disillusionment, and decline—key themes in his own work. Photographers often captured what words could only attempt to describe: collapsed rural economies, racial inequality, spiraling addiction, and political corruption.

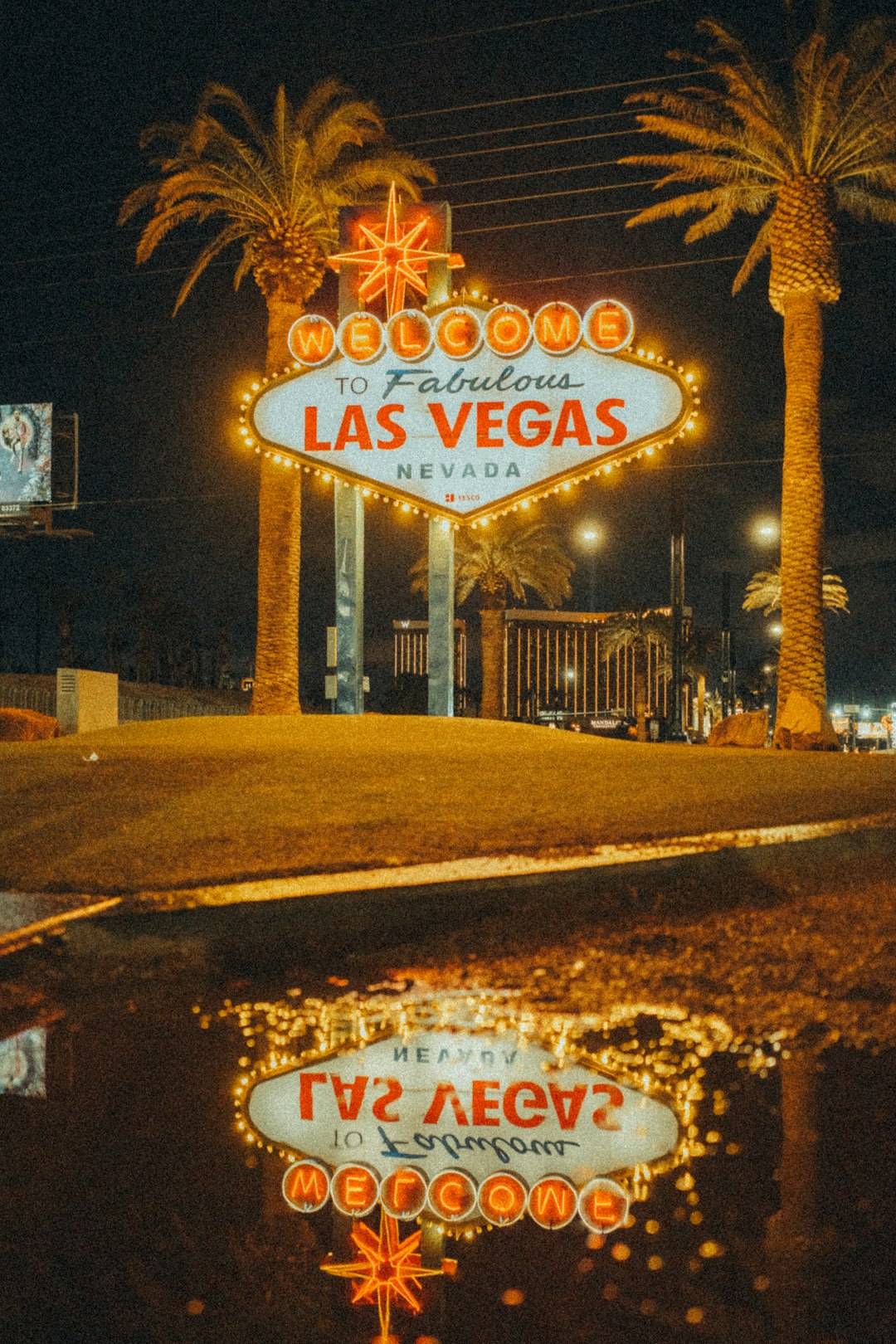

In his writings, particularly in works like Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Thompson lamented an America caught between moral bankruptcy and consumer delirium. Photographs that captured these themes served as supporting evidence to his claims, reinforcing his point that the surface mythology of America was at odds with its decaying core.

One can easily imagine that if Thompson were alive today, he would be a proponent of photojournalistic efforts like those of Matt Black or Nan Goldin, who continue to depict the underbelly of American civilization with unflinching honesty. To Thompson, these were not just artists—they were witnesses.

Camera as Collaborator: Working With Photographers

Though Thompson was rarely behind the lens himself, his collaborations with photographers were passionate and deliberate. In his partnership with Rolling Stone Magazine, Thompson worked alongside photographers such as Howard Bingham and Annie Leibovitz to ensure the visuals matched the intensity and irreverence of his journalism.

He didn’t just tolerate cameras on assignment—he relied on them. The photographs documented what his words distorted, exaggerated, or psychotropically skewed. Together, they offered a more complete and evocative portrait of reality, albeit still deeply subjective. This technique elevated not just his stories, but the standing of photojournalism in a rapidly evolving media environment.

Distrust of Corporate Media Imagery

Thompson’s embrace of photography did not extend to all forms. He was openly critical of corporate media and its use of photography to sanitize or manipulate public perception. Mainstream photography in glossy magazines or sanitized news outlets, in Thompson’s eyes, lacked the guts and vision to reveal the truth. Instead, it often served as visual propaganda—mainlining patriotism, consumerism, and compliance into the national bloodstream.

This view was aligned with his broader hostility to corporate journalism, which he believed had traded integrity for advertising revenue and editorial obedience. In a media world diluted by safe imagery and strategic omissions, Thompson’s ideal photography remained something fiercely independent—a rebellion in 35mm.

Legacy and Influence

Hunter S. Thompson’s perspective on photography continues to resonate in today’s media landscape. As smartphones turn everyone into accidental photojournalists and social media becomes a battleground for visual truth, his insights seem remarkably prescient. What would Thompson make of a world where livestreams replace cable news, and images of police brutality circulate within seconds?

Chances are, he would both celebrate and condemn it—celebrate the uncensored immediacy of the visual, and condemn the new forms of algorithmic sanitization that blur the line between documentation and spectacle.

Contemporary parallels to Thompson’s photographic ideals can be seen in:

- Citizen journalism: Visual reporting from protests and crises that bypass official media gatekeepers.

- Photo essays: Long-form, narrative photography documenting poverty, addiction, and resistance.

- Street photography: Candid moments that shed light on the authentic, messy human condition.

In these modern echoes, Thompson’s belief in the radical power of the image lives on.

Conclusion: A Shared Mission

Hunter S. Thompson may never have been a photographer himself, but he recognized photography not merely as an aesthetic practice, but as a vital force in the cultural bloodstreams of America. For every manic paragraph he wrote, there were images that told similar stories, just as wild, wounded, and dangerous.

His legacy invites us to view both journalism and photography as symbiotic weapons in the ongoing struggle to capture—or perhaps survive—the American experience. In a time when truth is once again under siege, his perspective offers a rebellious blueprint for how words and images can confront power and provoke thought.